- Home

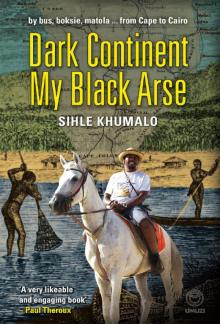

- Shile Khumalo

Dark Continent my Black Arse Page 13

Dark Continent my Black Arse Read online

Page 13

‘So are you Nkatha?’

I learned a long time ago that answering ‘yes’ or ‘no’ is not necessarily a good thing. ‘Mmm,’ I said, trying to keep calm. ‘As much as most of Inkatha members are Zulu, I think not all Zulus are Inkatha members.’

‘You have not answered my question,’ the Head of Consulate replied quickly.

At that moment the gentleman seated opposite me on the couch asked, ‘Do you smoke?’

I told him that I did not but I had puffed on a cigarette once or twice in my more youthful days.

The Head of Consulate, who was now paging through my passport, asked me another question: ‘Why did you go to Bangkok?’, referring to my trip to Thailand a few years back.

There was no specific reason why I had visited Bangkok except that it was the cheapest international destination I could find to visit as part of my 23rd birthday celebrations. Obviously, I could not state the truth. Instead I replied, ‘I wanted to experience the Thai culture, Sir.’

The other gentleman then asked me, ‘And why do you want to visit Ethiopia?’

The honest answer would have been: ‘Because from Kenya to Egypt the only safe route goes through Ethiopia and Sudan.’ But I could not say that, of course, so I mumbled something like: ‘A colleague of mine visited Ethiopia a few months ago and he liked it so much he convinced me that it is one of the countries I should visit before I die.’

At this the Head of Consulate looked at me and said, ‘OK. We will give you 30 days.’

I felt like standing up and hugging him. I had already given up on getting an Ethiopian visa and within an hour I was leaving the embassy with a visa that I had thought would, if I got it, take about two days to process. The bad news was I had 30 days effective from the issuing date to travel through northern Kenya as well as Ethiopia. Given the rumoured irregular modes of transport further north and the reportedly slow Ethiopian public-transport system, as well as the well-documented long waiting period for a Sudanese visa in Addis Ababa, I knew I had to cut short my stay in Nairobi.

From the Ethiopian embassy I walked to the city centre, past Uhuru Park, the one that was saved by Wangari Muta Maathai when then President Arab Moi wanted to build a 60-storey building there. Wangari, both environmental and political activist, was the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize, in 2004, for her efforts in sustainable development, mainly involving women planting trees. The park is indeed a green haven in the middle of a concrete jungle.

By the time I got to the bank I was saying to myself, Wow, if I thought the women in Dar were beautiful, I have to think again. The ladies in Nairobi looked even more stunning. They had a more sophisticated and cosmopolitan, yet natural, African look about them, like former Miss South Africa-turned-businesswoman, Bastsane Khumalo (née Makgalemele).

While I was gazing at the slim-limbed, elegant creatures I suddenly remembered that I had another small problem: the cash I had in hand was not enough to get me to Cairo. Changing money in Nairobi was not as bad as in Dar, however. Within two hours a bank had sorted me out and I had my US dollars.

After once again appreciating the gorgeous ladies of Nairobi, I decided to go to the museum. There is something special about museums: they give you insight into a country that you cannot normally get from a book. The National Museum in Nairobi has been operating for more than 70 years and its collections cover a wide range, from handicraft and cultural exhibits to Kenyan wildlife to history, starting from prehistoric times up to the Kenyan struggle for uhuru – freedom. It was the first time that I truly understood the loss of life exacted by the Mau Mau rebellion. By the time the revolt was suppressed in 1956, more than 13 500 black Kenyans and just over 100 Europeans had died. Out of that struggle, the man to emerge most strongly was Jomo Kenyatta.

Right next to the museum is the snake park. I don’t think anyone can be more terrified of snakes than I am; I’m one of those people who can’t even watch a snake on television. So, for obvious reasons, I steered clear of the place. I sat on a bench under a tree in the city gardens, enjoying the sight of people lounging on the green lawns.

Nairobi, I discovered, is not nicknamed the safari capital of the world for nothing. Almost everything in Nairobi is touristy: safari this, safari that, safari this, that and the other. Although I would have loved to visit the Masai Mara National Reserve, the most famous and most visited park in Kenya, it seemed as if prices were aimed at super-rich tourists. Considering that it was the time of the annual migration of wildebeest and zebra from the Serengeti plains to the lush grasslands, I am sure prices had been increased further to cash in on the two-month natural extravaganza. As with the South Luangwa National Park in Zambia, which I had missed out on because of the high admission price, I decided to give Kenya’s best animal reserve a miss. Thus I couldn’t see for myself the dozen different species – buffalo, eland, elephant, gazelle, giraffe, hyena, kongoni, lion, ostrich, topi, wildebeest and zebra – that they say can be seen all at the same time.

Before leaving Nairobi I decided to get a letter of introduction from the South African High Commission to use in Addis Ababa when applying for a visa to Sudan. One thing about this kind of trip: you learn, very quickly, to think ahead and be on your toes all the time.

The High Commission was about half an hour on foot from my backpackers. I hoped that, as at the Ethiopian embassy, I would be invited to the Head of Consulate’s office. But it was not to be. Instead, while my letter was being prepared, a forty-something lady came to talk to me through the window that shielded those behind the reception desk from those in front. She asked in Zulu where was I heading and why.

It was nice to be able to communicate in Zulu again. It was just basic chatting and it was good to see my people representing us in foreign lands. As she was about to leave she said, ‘Ndiyavuya ukukwazi. Uhambe Kakuhle’ – I am happy to meet you. Travel safely.

‘Ngiyajabula ukukwazi nami,’ I replied. ‘Ngiyabonga kakhulu, sisi’– I am happy to meet you too. Thanks a lot, sister.

Being the eternal optimist, I was hoping that maybe, just maybe, I would bump into a sexy young South African working at the High Commission. Or, even better, a home girl visiting Nairobi for pleasure, or perhaps business. Well, again, it was not to be.

As I left the building I knew that one day I would simply have to be my country’s High Commissioner in some exotic place like the Bahamas, Maldives or Fiji. It wasn’t a resolution, it was a dream. And dreams can come true: within two days of arriving in Nairobi, I already had my Ethiopian visa and a letter of introduction to be used in Addis when applying for my Sudanese visa. I knew then that I was on my way to fulfilling my childhood dream of travelling from Cape to Cairo. I found myself happily humming the words of Bob Marley’s song,‘Don’t worry about a thing,’ cause every little thing will be alright’.

Returning to the city centre later that day, I noticed a modern building named Integrity Centre. On closer inspection, I discovered that it housed the offices of the Anti-Corruption Commission. The small parking area next to building had a sign that read This is a corrupt-free zone. I’m sure they meant well, but for some people, including myself, it created a very bad impression.

Since it was my last night in Nairobi, I decided to have dinner at an upmarket restaurant to celebrate reaching the halfway mark of my trip. As I walked into the posh restaurant in the Hilton Hotel I spotted a fine-looking young woman sitting all alone. She was also looking at me with her big eyes while sucking a cocktail through a straw. Being such a faithful man to my fiancée, I totally ignored her while I placed an order.

Have you ever had the feeling that someone is constantly and continuously staring at you? That is what I felt. With reason. That woman had her eyes all over me when I went to dish from the salad valet, making me feel uncomfortable in a very pleasant way.

After downing my first beer, I started to feel bad about ignoring such a beautiful sister. When I looked up to order another beer, our eyes locked. That was it. I

went straight to her table. We had just started chatting when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned around and there was this Mike Tyson look-alike standing right behind me. The only difference was that he was pitch black. He asked me something in Swahili, pointing to the sister who also looked freaked out.

I just sat there looking straight into his eyes, pretending to be fine, whereas I was feeling shit-scared. Without another word the boxer type grabbed me by the scruff of my neck and pulled me out of my chair. Thank goodness, two waiters came over and pushed him away.

I headed straight for the door – not running, just walking fast and checking over my shoulder to see if Iron Mike was following me. As I was about to exit I looked back one last time and saw that he was arguing with the woman. I got into a taxi in order to get to my backpackers as soon as possible.

Nairobi, especially in the recent past, has experienced phenomenal population growth. As a result, there is heavy traffic congestion even at night. From the passenger seat in the front of the cab I kept looking at the side rearview mirror just to double-check that Iron Mike was not pursuing me as we were stuck in traffic literally a few metres from the front door of the restaurant. It was at that moment that I knew, for sure, I had to leave Nairobi.

Back at the backpackers, even the dog that assisted the guard with security duties at night wanted to bite me. I was more than ever convinced that I had to leave Nairobi the next day.

That night I tried having a local beer just to calm my nerves, but it tasted awful. I paid and left – I was still not used to the idea of having a beer and writing my name in the black book so they could charge it to my account, to be paid when I settled the rest of my bill. The problem was that no one monitored the process. You could, therefore, have quite a few beers without writing your name in the black book and no one would have noticed. You drank beer on trust at this particular backpackers.

I woke up the next day feeling lethargic. It had nothing to do with the previous evening’s Mike Tyson episode. It suddenly hit me: the last time I had had a bath was in Mombasa, three days ago. I was definitely not doing things I didn’t want to do, like I often did back home.

After a cold shower, I felt like a brand-new person. I went for a last-minute stroll in the city centre, past the City Hall and into City Square, where Jomo Kenyatta’s statue sits facing a courtyard and the flickering flames that guard this monument. I continued past Parliament. Needless to say, I had to wear a cap just in case I ran into Iron Mike. I didn’t bump into him, but I did bump into two beautiful ladies who made it very clear they were not interested in me.

In the afternoon, I headed for Eastleigh on the outskirts of Nairobi to catch a bus north. Eastleigh is a scruffy and neglected part of the city, inhabited mostly by Ethiopians, Somalis and Eritreans. I was much relieved when I was told that there was a bus going straight to the border town of Moyale. Ticket in hand, I made my way towards the bus. When it was pointed out to me, I could not believe what I was seeing – a converted truck pulling the shell of a bus, with everything expertly welded together. Being a converted truck, the passengers could not see the bus driver.

We left Nairobi at sunset.

I was aware that we were following a dangerous route. A month before I arrived in Nairobi there had been a massacre at Marsabit in which schoolchildren were attacked and killed. Marsabit lay on the bus route to Moyale. The bus, however, was not likely to be attacked, the cab driver who had taken me to Eastleigh reassured me, because it was owned by the bandits who were causing all the trouble in the northern part of Kenya.

For a converted truck, the bus was really speeding, probably because it would be dark soon. As we were fast approaching the equator, twilight – the time just before sunrise and just after sunset – was very short, lasting only about five minutes. To me the change from light to dark looked abnormal and unnatural. And crossing the equator by air is very different from crossing it by road. Unless you are the pilot, you are never sure of the exact moment of crossing the ‘big red line’ when you are flying, whereas you can stop right on top of nought-degrees latitude if you are travelling by road. Bam!

Inside the truck-bus the passenger cab was soon very dark, but instead of worrying about that I found myself thinking that if only there were an open-minded woman sitting next to me my fingers could do the walking/talking. Unfortunately, I was seated next to an old Muslim woman with a five-year-old boy on her lap, her head covered with a black scarf.

Our first stop was at the small town of Nanyuki, located right next to the equator. Actually, the airport sits on one side of the equator while the town, which is dominated by a huge market, lies right on top of the equatorial line. Tourists who come to Kenya to view wildlife end up coming up to this old settler town just to have their photos taken next to the yellow board at Nanyuki – This sign is on the Equator – which confirms that they are now standing exactly halfway between north and south. Although I know that the equator is an imaginary line, I found myself subconsciously looking for that straight line that cuts the globe into two equal hemispheres.

Other tourists come to Nanyuki as a transit point on their way to trekking on Africa’s second highest mountain, Mount Kenya, which lies between 40 and 50 kilometres to the southeast, as the crow flies.

We continued north and stopped again, just before midnight, in a very seedy-looking town named Isiolo, situated, apparently, on the border between the fertile highlands and the desert – it was too dark to see. From Nairobi to Isiolo we had travelled on a very good tarmac road, a puzzle because I had been told, back in Nairobi, that the road to Moyale was bad. Just after Isiolo, however, the real African journey began.

I had expected that somewhere along the line we were going to drive on gravel, but I did not think it would be like this. The whole body of the bus started shaking and vibrating heavily as we hit the road. I found it impossible to sleep, although it was after midnight. The bus was still speeding and it felt as if I were sitting on a jack hammer. In addition, the windows were rattling non-stop. Under those conditions sleeping, for me at least, was totally impossible. Other passengers, however, were in dreamland, judging by the deep breathing and the occasional snore.

In the middle of nowhere, the bus stopped to pick up an elderly Masai man. Within minutes this Masai, who was seated next to the aisle a couple of rows in front of me, decided to start singing at the top of his voice. Obviously I did not know the song, but I could tell that he was repeating the same line over and over again. I could hear, as well, that he was miles off the right tune. He had a hoarse voice – he sounded like Eric Clapton trying to sing opera.

It was Friday night/early Saturday morning and it dawned on me that, had I not made the decision to leave my job and backpack to Cairo, I would be sleeping comfortably at home, as is normal in the middle of the night. Instead, my whole body was vibrating in a truck converted into a bus while I was forced to listen to a Masai singing loudly out of tune. For the first time on the trip I regretted having left the comfort zone. The shaking was so bad that, although the luggage on top of the bus had been tightly fastened, the driver’s three assistants had to take turns to check that nothing had fallen off the roof rack.

We arrived in the dusty town of Marsabit in northern Kenya, 550 kilometres from Nairobi, just after sunrise. We spent two hours waiting in this town, supposedly a fascinating hill oasis in the desert, parked outside an old, run-down building, the most striking feature of which was its peeling red paint. I thought we were waiting to join a convoy as I had read that vehicles going from Marsabit to Moyale travel, for security reasons, in convoy. To my surprise, there was neither armed guard nor convoy when we left two hours later.

As if that were not enough, the bus broke down about an hour outside Marsabit. Something had gone terribly wrong with its wheel alignment. We were ordered to disembark and that is when I got the shock of my life. The reason why the bus was shaking and vibrating so badly was because we were more or less driving on rocks. That also explained why

a converted truck was used instead of a bus. No bus could survive continuous driving on such a rocky surface.

Within half an hour, after one of the assistant drivers had used a rope to tighten something on the inside of the right-front wheel, the journey to Moyale was resumed.

The next stop was in a small town called Torbi, which is actually not a town but two shops. I was standing around looking at the desert when Saddam, a local guy in an off-white robe, approached me and asked in no uncertain terms, ‘What do you want, my friend, a gun or drugs?’

After turning him down politely, I knew it was time to get back into the hot bus and wait there for the other passengers to finish having lunch and quenching their thirst in the only restaurant in town. (All the shaking and vibrating had made me lose my appetite.) It was a very hot and dry day. I sat back and reflected on the distinct difference between the south and the north in Kenya: the easygoing Swahili (read ‘black African’) culture of the south and the austere atmosphere of the hot and arid north, where people follow a nomadic lifestyle and move around with their camels, cattle and other domestic animals. They also speak a language in the north that sounds totally different from the languages spoken in Nairobi and Mombasa. It was as if I were in another country.

Resuming our journey, we encountered three roadblocks between Marsabit and Moyale. Just after the second one, soldiers in a 4x4 overtook and stopped us. Without a word they arrested one of the driver’s assistants who was at the time seated on top of the bus checking the luggage. He was taken to the 4x4 and the soldiers left with him. The passengers were talking under their breath to each other. Certainly none of them dared to challenge the soldiers. Neither did the driver.

Soldiers at the third and last roadblock wanted us to produce identity documents or passports. Quite a few passengers had neither. Naturally, the passengers without documents had to make a plan with the soldiers. In front of everyone they paid the soldiers money, how much I do not know. What interested me more was how fully accepted bribery was. Not that you could blame the people who paid the bribes. At the mercy of soldiers in the middle of nowhere, you do not insist on your rights.

Dark Continent my Black Arse

Dark Continent my Black Arse